ABOVE: Dancers merge with puppets in a scene from that show.

One summer afternoon on Kauai in 1820, King Kaumualii and Queen Kapule summoned two young missionary couples to their home near the mouth of the Waimea River. The Whitneys and the Ruggles had arrived on the island just a few days earlier, and the monarchs had arranged a fun surprise for them. When the guests entered the royal household, an elderly man seated on the floor began to drum and chant. Behind him stretched a kapa (bark cloth) curtain. Above it appeared six "idols," as one of the missionaries called them, which began to move in time to the music.

The missionaries were not amused. In her journal entry recording the scene, Mercy Partridge Whitney wrote, "We were soon convinced of the folly & vanity of such an exhibition, & as soon as politeness would permit, took leave of the King & Queen and returned home." The negative review of Kaumualii's well-intended surprise is the first documented account of a little-known form of hula called hula kii—a.k.a. Hawaiian puppetry.

Abhorring hula in all its forms, Hawaii's missionaries suppressed it with infamous zeal. Of course, hula never really went away, and neither did hula kii. But while hula came roaring back, hula kii has remained an obscure genre. Lately, though, it's been having a moment.

Last summer, in conjunction with the Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture, hula's dancing puppets seized the limelight. They danced on the front lawn of Capitol Modern, the Hawaii State Art Museum, and for the rest of the year occupied its first floor in a curated exhibit. They appeared at talk-story sessions and turned up on local TV news. They flew back and forth over the Pacific Ocean to stage an elaborate theater production in Honolulu and San Francisco.

Behind this upwelling of hula kii energy lies a small collective of Hawaiian puppetry practitioners working with the Hula Preservation Society. The Kaneohe-based nonprofit serves mainly as an oral history archive, but since 2009 it's been a driving force in perpetuating hula kii in the twenty-first century. "It is a passion project," says Maile Loo-Ching, the archive's executive director. "It's about educating the wider community and educating the hula community, too—because even a lot of hula people don't know about hula kii, by no fault of their own."

The Hula Preservation Society's Maile Loo-Ching (right) works to promote hula kii, a.k.a. Hawaiian puppetry. Here she shares a moment backstage with dancer Meridith Kawekiu Aki before a hula kii performance in San Francisco.

Just as the Hawaiian word "kii" has many meanings—including statue, image, drawing, doll, idol and petroglyph—hula kii has many variations. A person and a kii might dance together, or the kii might dance above a screen with its person hidden below. The kii might be a hand puppet, a finger puppet or an enormous puppet the dancer wears as a body mask. The kii might be a carved figure made to dance by a person seated behind it. Or there might be no kii at all, and the dancer simply assumes the form of one. "There's so much diversity and nuance and variety in hula kii, it's quite extraordinary," Loo-Ching says. "But that's how hula is, too."

Loo-Ching's first encounter with hula kii came in the late 1990s when, after returning home from Stanford University with a degree in artificial intelligence, she became a hula student of Winona Beamer, the renowned Hawaiian educator, musician and kumu hula (hula instructor). Hula kii was one of several rare hula genres that Auntie Nona, as Beamer was widely known, performed and taught. As a child, born in the 1920s, she had seen her great-grandmother perform it, squatting behind a tall kii, chanting and laughing as she made it dance on the floor. Her grandmother showed her a different approach, where dancers operate hand puppets with heads made from young coconuts. That's the style Auntie Nona adopted.

Auntie Nona included hula kii in broader hula programs built around historical themes. In the late 1940s she toured the United States, Canada and Mexico in an old hearse with her halau (hula troupe) and their coconut-headed companions, performing a show depicting the evolution of hula from pre-missionary times into the twentieth century. In later years she incorporated hula kii into community enrichment programs, using puppets to celebrate Hawaiian culture and bring myths and legends to life. "She knew that kii would be a way to really draw people in," Loo-Ching says.

Auntie Nona and Loo-Ching jointly founded the Hula Preservation Society, which grew organically out of an interview with the teacher that the student videotaped for reference. Before long, scores of Auntie Nona's hula world peers were sitting for Loo-Ching's camera, talking about hula history and Hawaiian life in general in the twentieth century. Auntie Nona grew so fond of her student she made her a hanai, or adoptive, daughter. But Loo-Ching was not Auntie Nona's hula kii protege. That was the role of another student, Mauli Ola Cook.

Originally from Connecticut, Cook came to Hawaii to study modern dance at the University of Hawaii in the late 1970s. Later, with funding from the Hawaii State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, she did an apprenticeship in hula kii under Auntie Nona. During a year of long weekends, Cook formally learned from her "beloved auntie and mentor" all aspects of hula kii, from gathering coconuts to writing and performing skits and mele (song).

Cook settled on Kauai and became an arts educator and storyteller. She has shared hula kii with generations of schoolchildren, as well as library patrons, hospital patients, youth correctional facility residents and cable TV audiences. She and her hula puppets have been at it for more than thirty years, albeit not nonstop. "I'll let the kii rest for a couple of years sometimes, and then they start squawking at me from under the bed—’Auntie Mauli! We want to get out of the box! Let's do something!'" Cook says.

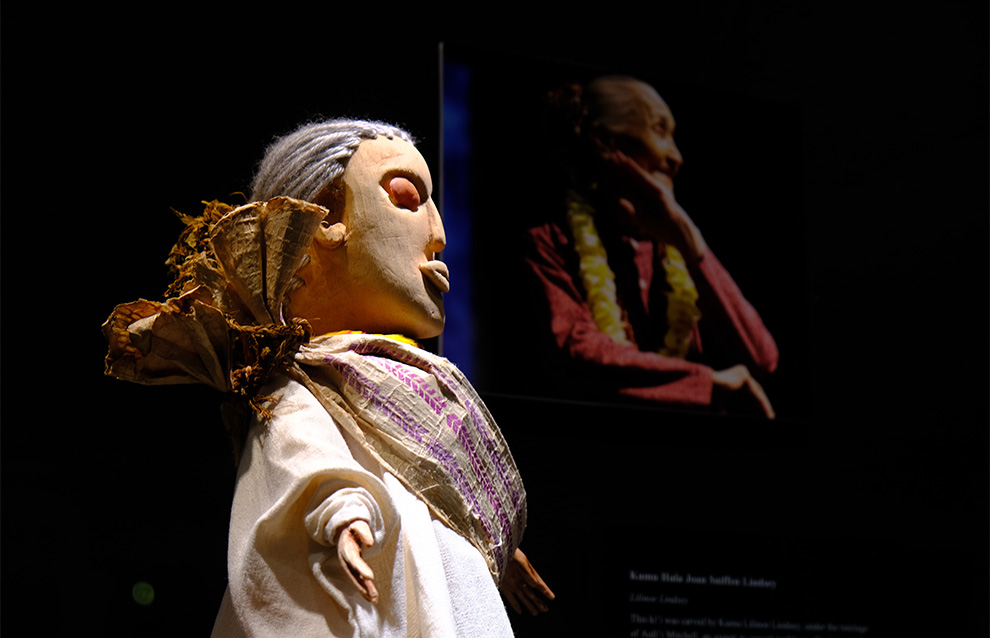

Hula kii may include crafted hand puppets, carved-wood figures and large masks the dancers can operate from within. Above, a kii on display at Capitol Modern in 2024, in the likeness of the late kumu hula (hula teacher) Joan Lindsey, whose photo is in the background, carved by her niece and protege, Lilinoe Lindsey.

In 2018, as an eruption of Kilauea was reshaping Hawaii Island's lower Puna coastline, nearly a thousand people descended upon Hilo for an international hula conference, Ka Aha Hula o Halauaola. Among them was a kumu hula from California, Mahealani Uchiyama, who signed up for one of the conference's many workshops. It was a three-day training in hula kii, led by Cook and Loo-Ching. They covered how to create kii, bring them to life and dance with them, all in the Beamer tradition. Uchiyama was enchanted. "I just thought they were the coolest thing," she says. "And I wondered, 'How can I bring this to my halau and get it implanted there?'"

Back home, Uchiyama got grant funding to enlist Cook and Loo-Ching to train her hula dancers in hula kii. Before long her Mahealani Uchiyama Center for International Dance in Berkeley was abuzz with women sewing tiny costumes and hot-gluing seashell faces and raffia hairdos onto little coconuts. "You can't just go to ‘Aloha Hula Supply' and buy a kii," Uchiyama says. "If you're going to dance with a kii, you have to make it. You personalize it, and it becomes an extension of yourself when you dance."

Her dancers' two years of hula kii training, both live and on Zoom, culminated in an elaborate theater production, a hula kii extravaganza called Wai Ola: Aukele and the Waters of Life. Cook wrote the script, basing it on the epic Hawaiian folktale of Aukelenuiaiku, a hero whose journey is fraught with peril, including ten jealous brothers who want him dead. The brothers are played by ten hand puppets operated by ten of Uchiyama's dancers. Aukele is played by both a live dancer and a puppet. Cook narrates and Loo-Ching serves as hoopaa, the chanter and drummer, helping to build a lush soundscape for the ancient story.

In one of the attempts on Aukele's life, his brothers throw him into the pit of a man-eating lizard-woman, Mooinanea. But rather than devour Aukele, she sees his goodness and offers him help. Uchiyama operates Mooinanea. The original puppet cast in the role—which had gray dreadlocks much like Uchiyama's—proved hard to work with. With a head made from an oversize gourd mounted on a pole, it towered over her like a giant cake pop in a dress. It was top-heavy and unwieldy. Before the show played in Honolulu and San Francisco in 2024, Uchiyama turned to Aulii Mitchell, a kumu hula and master hula kii practitioner on Hawaii Island, for help.

Ordinarily, the hula kii Mitchell makes are small, hand-held figures carved from wood. His Mooinanea was a departure. Eight feet tall and more lightweight and lizardlike than the original, it exemplifies the body-mask style of hula kii. Uchiyama disappears inside of it. She's seen only when Mooinanea bestows gifts upon Aukele, and then it's only her hands that appear.

Four kumu kii, or masters of Hawaiian puppetry, comprise the Hula Preservation Society's hula kii collective. Seen above at last year's Hula Kii Day presentation at the Capitol Modern, they are (from left): Kaponoai Molitau, Taupouri Tangaro, Aulii Mitchell and Mauli Ola Cook. PHOTO BY AKAU MEDIA

Mitchell first encountered hula kii in the 1980s when his mother, Aana Cash, a master kumu hula (and childhood friend of Auntie Nona's), sang to him a mele that her father had sung to her. She knew it was for hula kii, but that was all she knew. Mitchell was in his early twenties then, already a kumu hula himself, teaching under his mother. "She gave me the song and challenged me to find the true meaning of hula kii," he says.

He started in a storage room in Honolulu's Bishop Museum, where he saw a hula kii family of three—a mother, father and infant—all carved from wood, probably in the nineteenth century. "After seeing the originals," Mitchell says, "I was lost in it." He re-created the characters in papier-mache, took a seated hula position behind them and taught himself how to make them dance. Working with the Elderhostel program in Hilo at the time, he had a ready-made audience to help hone his performances. When humidity eventually took its toll on his papier-mache partners, he laid them to rest.

Before making his next set of kii, he traveled to Washington, DC, to see a group of six Hawaiian puppets at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History. Representing stock characters from Hawaiian folklore, they have names like Nihiaumoe (Midnight Prowler) and Makakuikalani (Royal Boaster). They once danced for kings, from King Kamehameha III to King David Kalakaua. In 1886, during Kalakaua's fiftieth-birthday jubilee, they stole the show during the intermission of a four-act drama at the Honolulu Opera House. Rising up from behind a screen, they danced hilariously to the beat of the hoopaa. The crowd demanded an encore.

These are the same puppets that University of Hawaii at Manoa anthropologist Katharine Luomala stumbled upon in 1966, when she opened the wrong drawer at the Smithsonian and found six little faces looking up at her. That surprise encounter launched her on a scholarly study of hula kii resulting in her 1984 book, Hula Kii: Hawaiian Puppetry. It was this book that led Mitchell to meet these royal puppets himself. "When I saw them it was literally like they were lying down sleeping," he says. "I felt attached to them immediately. I wanted to awaken them."

Each is about a foot tall with movable arms, no legs and long gowns that hide the puppeteers' arms. Back in Hawaii, Mitchell took a mallet and chisel to some driftwood and taught himself to carve kii like the royal puppets at the Smithsonian. "When I started they looked really spooky," he says. "Then they started to look like me, and then they took on their own personalities. And now I'm able to go between the world of humanlike and godlike."

Hula kii performances can range from the sacred to the comical. Above, Tangaro performs an oli (chant) before dancing with his hula kii, which he wove from wicker and modeled after an ancient kii in a museum. "His name is Paulihiwakalaniohilo," Tangaro told the crowd. "But I call him Frank." PHOTO BY SFCA AND THR LVRG GROUP

On the front lawn of the Hawaii State Art Museum last summer, a curious crowd gathered for Hula Kii Day. Loo-Ching and the four masters of the Hula Preservation Society's hula kii collective presided, with a few dozen hula dancers assisting.

Cook told stories and danced sweetly with hand puppets and dancers from Kauai and Oahu. Mitchell drummed on an enormous ipu (gourd) as students of his from various points on the globe performed seated hula, moving the jointed arms of little wooden figures they themselves had carved. Among their mele was the song passed down from Mitchell's grandfather.

A kumu hula from Maui, Kaponoai Molitau, led his dancers through both the seated form of hula kii and the body form. In one number the dancers stood with their knees bent and unmoving, as if they themselves were statues of Hawaiian gods. Moving just their arms and faces, they illustrated the oli (chant) "Auwe! Pau Au i ka Mano Nui, E" (Alas! I've Been Consumed by the Great Shark). It's based on a Hawaiian proverb noting that the blossoming of the wiliwili tree coincides with shark mating season. "So when you see the pua [flower] wiliwili blossom here in Hawaii," Molitau told the audience, "no go jumping in the ocean unless you want to mate with the mano."

Taupouri Tangaro, a kumu hula from Hawaii Island, took the stage with a tall black kii woven from rattan. "His name is Paulihiwakalaniohilo," Tangaro said. "But I call him Frank." Sitting onstage behind Frank—who somewhat resembles a laundry basket with mother-of-pearl eyes and a mouthful of dogs' teeth—Tangaro danced him to life, lending Frank his arms as if they were Frank's own. In another number, Tangaro took the form of a kii himself in a humorous, unapologetically risque dance—the kind of thing that would have had missionaries looking for the earliest opportunity to excuse themselves.

As part of the thirteenth quadrennial Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture in June 2024, Hula Kii Day drew a demographically diverse audience from Hawaii and other Pacific islands. The festival theme was "Hooulu Lahui: Regenerating Oceania." Before Tangaro performed, he told the crowd that hula kii never died—"It just went to sleep for a while, and we're the people who are waking it up." In his closing remarks Tangaro circled back to connect hula kii with the Hooulu Lahui theme, telling the crowd, "There's a whole lot more of our culture that's waiting for you to wake it up."